By Jean Willoughby

When I began working in agriculture almost a decade ago, I rarely heard the word equity in any other context than lending. But I heard the word discrimination a lot, a whole lot.

It’s not too surprising. For most of this time, I’ve lived and worked in North Carolina, a state home to many of the black farmers who brought (and won) the largest civil rights class action lawsuit in our country’s history against the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the remaining funds of which have only recently been dispersed. Discrimination proved to be so widespread within the USDA that the department has spent much of its recent history in court or settling claims not only with tens of thousands of black farmers but with Native American, Hispanic/Latino, and women farmers.

At my former job at a nonprofit that advocated for family farms, I heard first-hand many painful stories from farmers who had experienced the frustration and humiliation of being discriminated against. Our farm advocacy staff often discussed and worked to address issues of discrimination, whether at the hands of lenders, local boards and committees, or various USDA agencies. In 2012, hoping to contribute, I launched a major research project, an unpublished 40-page report with a collection of farmer interviews and case studies tentatively titled, Justice Delayed: Documenting Discrimination in U.S. Agriculture. As I conducted more research, however, it became clear that we were examining effects, not causes, and that our focus on discrimination was incomplete.

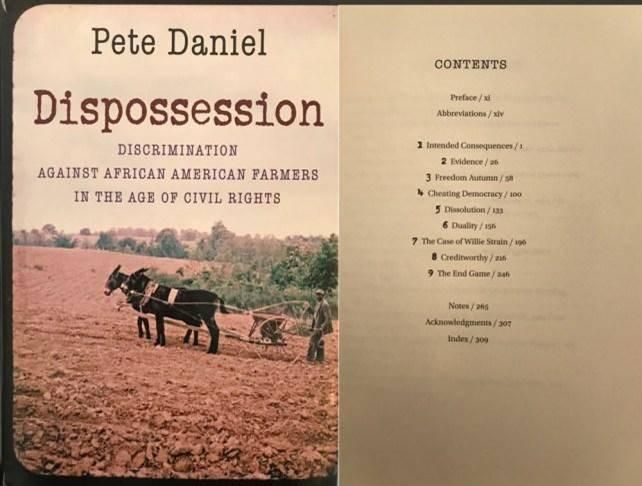

In 2013, former Smithsonian historian Pete Daniel published a remarkable and painful chronicle of how black farmers lost the majority of their land holdings during the years of the Civil Rights Movement. “Between 1940 and 1974, the number of African American farmers fell from 681,790 to just 45,594–a drop of 93 percent.” — Dispossession: Discrimination against African American Farmers in the Age of Civil Rights, via UNC Press

Discriminatory actions committed by USDA employees have certainly been prevalent and deserve to be addressed, but discrimination at this large a scale is of a different order of magnitude. It’s hard to believe that individual acts of discrimination alone could be responsible for pushing generations of farmers of color and indigenous farmers out of production and off their land. Institutional or system level policies and practices, or the lack thereof, must play a role in allowing such catastrophic losses of land and livelihoods to happen.

Perhaps ironically, the settlement era left a lot unsettled in U.S. agriculture. Without an examination of the historical context, institutions, and systems that gave rise to the many farmer lawsuits, we cannot begin to understand what led us to the vast inequities we see in agriculture today nor address them. To go beyond the frame of discrimination and the arguable achievements of the settlements (which overall brought forth monetary relief, not structural change), we need to develop an analysis of how our food and agriculture systems may actually work to create and maintain inequity.

Getting to the Groundwater

After a couple years of working primarily in economic development with farmers, cooperatives, and other collaborative farming enterprises, I got involved in farmland preservation as a way of working on what I saw as the structural issues shaping the future of our food system. I joined the team at Agrarian Trust, first as a founding advisory board member in 2013, and about a year ago came on board as our Organizational Development Director.

In 2016, I started attending Phase I workshops with the Racial Equity Institute. Last spring, after going to a Phase II workshop, I was invited to join the team, starting as a trainer-in-training and later as a trainer and organizer. It’s been an honor and a pleasure to work with such a dynamic team of trainers who come from fields ranging from business to medicine, to education and psychology. I’ve found their understanding both helpful and relevant to our efforts at Agrarian Trust to develop equitable models for land access.

Inspired by the work of Dr. Camara Phyllis Jones, trainers at the Racial Equity Institute developed an allegory to help explain how racism persists in our society despite our best intentions and efforts to treat people fairly. They refer to this story as “The Fish and the Lake,” and the 30-second version is this:

If you walked past a lake and saw a fish floating belly up dead in the water, you might wonder what happened to that fish. But if the next day you walked past and saw thousands of fish floating belly up, your immediate question would probably be, ‘What’s wrong with the water?’ Going further, if you saw several other lakes in your region where the fish were floating belly up in large numbers, you might be even more confused, concerned, and eager to know what was happening.

Without more information to go on (or a degree in Hydrology), you might feel pretty stumped. That’s because more than 95% of the freshwater on Earth is in the groundwater, deep below the surface of our lakes, rivers, and streams and hidden from sight. It’s not something we usually give much thought, but it has a major impact on all of our lives.

Today, there are millions of “fish” struggling for their lives in all of our systems and institutions, from the food system to the school system. However, most of us are so focused on helping individual fish navigate and survive, that we struggle to meaningfully address our systems or understand the deeper, interconnected issues beneath these outcomes.

By building on this allegory, the Racial Equity Institute’s “Groundwater Approach” offers a powerful metaphor to help explain how living in a racially structured society causes racial inequity.

Their analysis is based on three fundamental observations:

● racial inequity looks the same across systems,

● socio-economic difference does not explain the racial inequity, and

● inequities are caused by systems, regardless of people’s culture or behavior.

They also observe that every system or institution in our country generally uses a different technical term to describe the same problem, whether it’s the “achievement gap” in education, “health disparities” in healthcare, or “historically underutilized business” in commerce, and the list goes on. In agriculture, the USDA uses the term “socially disadvantaged groups,” to refer to a defined list of racial and ethnic groups and women. With such a multitude of different terms, it’s no wonder we struggle to communicate about the inequities in our systems, let alone work together across systems to address them.

Shared Analysis & Building Collective Power

Due in part to our lack of shared language, knowledge, and analysis, we in the farming and conservation communities often find ourselves ill-equipped to address some of the most critical questions that impact our work for equity. For instance, even after such major legal settlements with farmers of color, why do white people own 98% of all farmland, which is more than 40% of the land, in the United States?

To even begin to answer this question, we must ask others:

Why do we have such a large racial wealth gap in the United States? Why is this gap not closing but in fact widening, showing “no signs of closing” in our lifetimes?

Why is it that economists at our major research institutions can confidently project that the median household wealth for black families will fall to zero by 2053? (And that Hispanic/Latino household wealth will fall to the same level by around 20 years later?)

Why, in the decades since the significant victories of the Civil Rights Movement, are so many of our communities and schools undergoing a process of resegregation?

All of these questions are interconnected and have everything to do with how we work to create equity within our food and agriculture system.

As a nation, we’ve been contending with these ‘whys’ for a long time, but our ability to answer them has been diminished by a lack of training in the historical roots of racism. With such an understanding, we could develop tools and approaches that are up to the challenge of addressing its ongoing impact.

It’s true that many organizations in food and agriculture now acknowledge racism as a root cause of inequity. At the same time, we lack a shared set of working definitions and an understanding of what racism is and how it functions. If we want to achieve not only diversity and inclusion but also equity and justice, it’s critical that we build a shared understanding of racism as a system of advantage.

Looking Forward: A Groundwater Approach to Land Access

I have no doubt that Agrarian Trust’s commitment to dismantling racism and systems of oppression in land access benefits from the expertise offered by the Racial Equity Institute. The workshops also give us an opportunity to reach a wide variety of communities and like-minded land owners with our research and perspective on the history and future of our food system, land ownership, and the importance of developing equitable approaches to preserving farmland.

How we collectively organize for the power to create equity remains a key question. As we move forward at Agrarian Trust, we’ll have to ask ourselves and our partners how we might bring together work for land access and farmland preservation with organizing for racial equity and social justice. Put another way, we need to ask how we work not just in helping individuals with farmland preservation and land access but in creating broader, structural change that will ultimately benefit all of our communities, particularly those historically excluded from having access to land.

Part of what we have proposed is to develop innovative land access models that embody democratic land stewardship. But how will we know if these will be robust enough to take on the challenges of inequity? We’ll have to continue to work diligently, humbly, with our ears and eyes open to new insights in order to develop and sharpen our understanding. With this commitment, we can begin to incorporate a racial equity analysis into all of our efforts.

Organizing for racial equity not only strengthens our mission and those of our many partners in this field but ought to be a defining aspect of our collective work for equitable land access for the next generation of farmers.